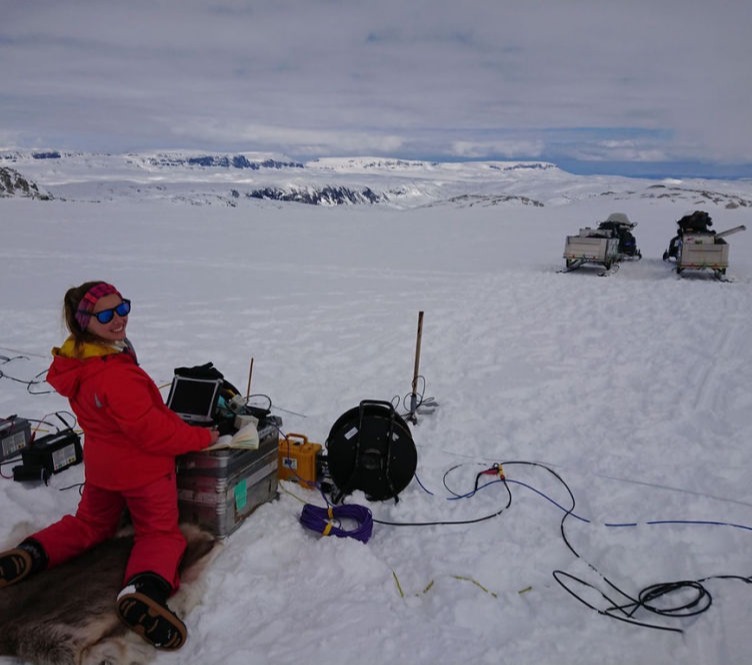

A beautiful day at Finse, Norway

These three reasons combined meant not only was

I able to apply for funding to support my trip

to Norway, (a BIG thank you to EU Interact) it

also meant, due to the accessibility of the

glacier (in comparison to perhaps… Antarctica),

the logistics of testing a geophysical survey

that might not work were relatively easy.

The

plan was to have two field seasons out in

Norway, the first in 2018, where I would scope

out the best places on the ice cap for my

research where there was known firn coverage,

and do some test surveys, and the second a year

later in 2019, where I would collect my final

dataset.