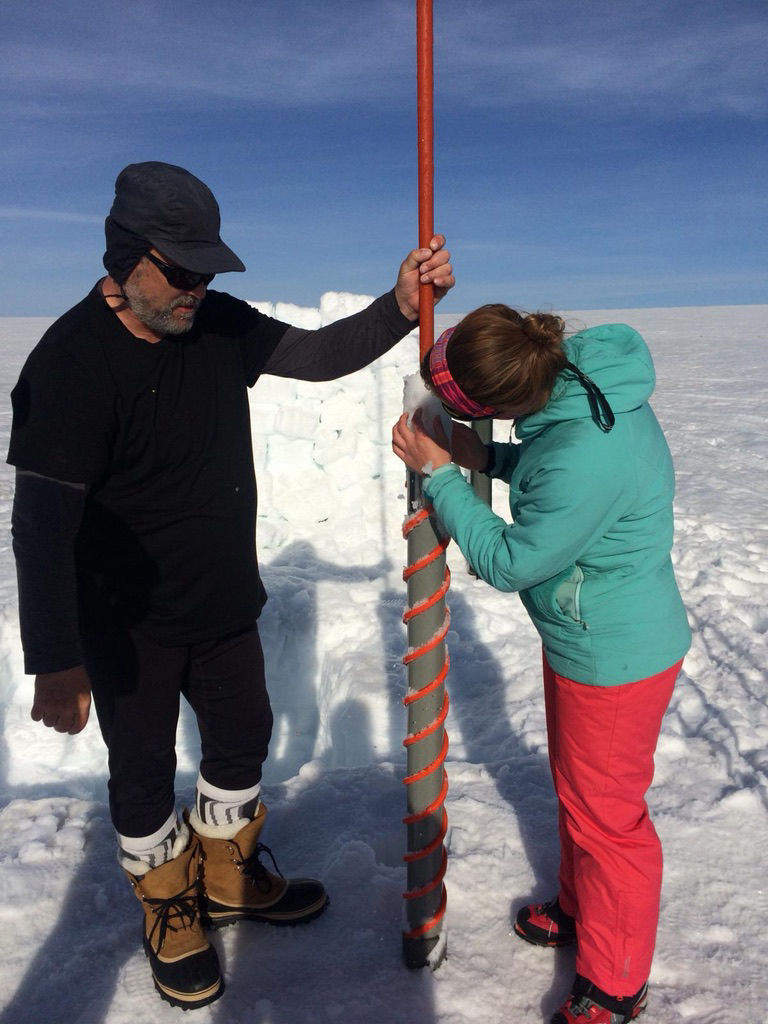

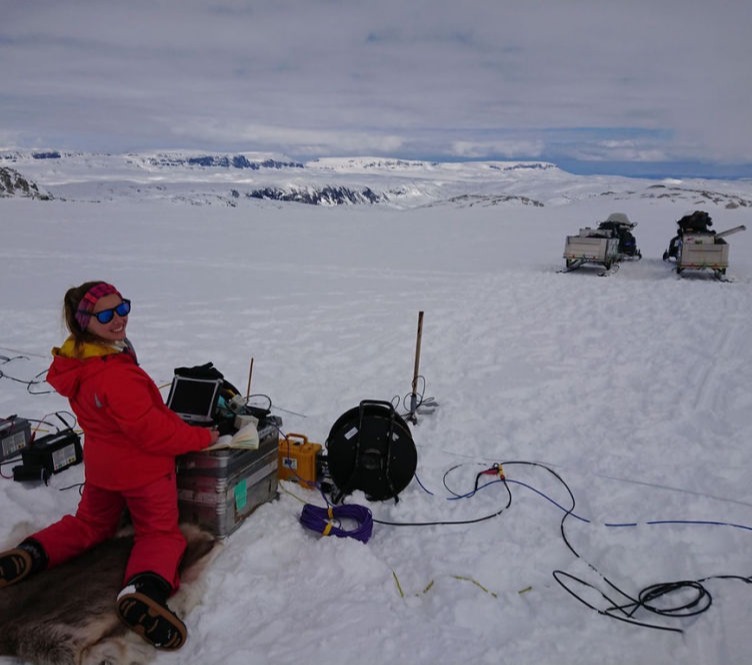

With our good data day behind us, the next day was a quicker start, with all the equipment already on the ice cap we just had to get up there and shoot the downhole seismic. The weather wasn’t as nice as we’d anticipated, but as it had stayed cold, it was safe to get to the ice cap. Once there, it was just a case of laying out our geophones around the borehole and using our downhole seismic source to acquire the data. Remarkably, for the first time in two field seasons, everything, went smoothly and to plan! With spirits high, and a few more bits of ice collected, we headed off the ice cap in a few ferried shifts, taking the equipment back to base, and took a deep sigh of relief. Two years of planning for data acquisition had all come together! The rest of the week saw the warm weather return, meaning the route to the glacier became near on impossible to traverse, unless the skidoo had suddenly grown wheels to get over all the newly appearing boulders. Meaning we were limited with what we could do, but sledging on station was always an option.

It’s clear to see from two fieldwork trips to Norway, that even with the best intentions of planning, things don’t often go the way you expect! None the less, I had two fantastic field seasons, with great company, amazing food, and a few awesome datasets collected!

I want to say the biggest thank you to everyone who has helped over my two field seasons, most notably Adam Booth for being the power behind the seismic sledgehammer. A big thank you also to Siobhan and James Killingbeck, Hannah Watts, Benedict Reinardy for their help with acquiring the seismic line. Bryn Hubbard and Katie Miles, for their help with drilling the borehole. And Kjell Magner for his logistical help on the icecap, meaning we didn’t end up in a crevasse. And of course, the biggest thank you to Marits, for all the amazing food she cooked to keep us sustained each day! And finally, thank you to the INTERACT team for funding this fieldwork.